In their strategic predictions for 2020, Gartner announced that the Internet of Behavior is something we’ll become increasingly aware of—and that we might have to grapple with as a society.

Soon the IoB will be prevalent. By 2023, they predict that the individual activities of 40% of the global population will be tracked digitally in order to influence our behavior. That’s more than 3 billion people! The IoB will challenge “what it means to be human in the digital world”. You could say it this way: we’ve moved beyond merely adopting technology to considering its ramifications.

So, what is this Internet of Behavior? Is it all good or all gloom and doom? Let’s take a look.

Understanding IoT

The Internet of Behavior extends from the Internet of Things (IoT), the interconnection of devices that results in a vast variety of new data sources. This data might be specific to you as a customer—data you’ve provided through a company’s app. But, more often, companies are gathering non-customer information by “sharing” across connected devices.

A single device, like a smart phone, can track your online movements as well as your real-life geographic position. It’s not difficult for companies to link your smart phone with your laptop, your in-home voice assistant, your house or car cameras, and maybe your cell phone records (texts and phone calls). Suddenly, companies can know a lot more about you—your interests, dislikes, the way you vote, and the way you purchase.

Companies are increasingly using such information to inform how they sell, but it’s not all targeted advertising. Data reaped from the IoT can be used for other reasons:

- Organizations can test the effectiveness of their campaigns, both commercial and non-profit.

- Health providers can measure the activation and engagement efforts of patients.

- Policymakers could even personalize content, affecting laws and current programs.

The IoT’s power is its scale, which is already enormous. Contentstack estimated the entire IoT in mid-2019 to include 27 billion devices. By 2020, they predict 75 billion devices will be part of the IoT. For Americans, that breaks into an average of five connected devices per household.

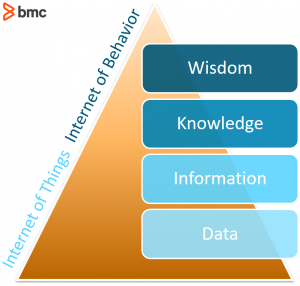

Consider the IoT the bottom of this pyramid, gathering the data and perhaps turning it into information. The IoB, then, attempts to turn that information into knowledge.

Internet of Behavior: extending IoT

Companies using the IoT to get us to change our behaviors isn’t really about the “things” at all. As the IoT links people with their actions, we’ve verged into the Internet of Behavior. Consider the IoB a combination of three fields:

- Technology

- Data analytics

- Behavioral science

We can break behavioral science into four areas we consider when we use technology: emotions, decisions, augmentations, and companionship.

As companies learn more about us (the IoT), they can affect our behaviors (the IoB). Consider a health app on your smartphone that tracks your diet, sleep patterns, heart rate, or blood sugar levels. The app can alert you to adverse situations and suggest behavior modifications towards a more positive or desired outcome.

For now, companies mostly use the IoT and IoB to observe and attempt to change our behavior to achieve their desired goal—to purchase, typically.

Marketers and behavior scientists tend to agree that this personalization is key to a service’s effectiveness. The more effective a service, the more a customer will continue to engage with it, and even alter their behavior because of it. Understanding that this personalization provides value to us, customers might still avoid it because it feels creepy. This psychological discomfort can cause us to avoid it, a tendency known as the ostrich effect.

Individual value, company gain

The IoB influences consumer choice, but it also redesigns the value chain. While a majority of consumers indicate unhappiness at giving away their data “for free”, many are satisfied with doing so as long as it brings them an added value.

This gives companies we don’t historically love engaging with, like insurance providers and banking, the opportunity to change their image. Pulling from the IoT, they can provide data-driven value. Optimize your individual premium based on health habits or a clean driving record. Nudge you towards more saving, investing, or other long-term financial goals.

Remember our health app that tracks your diet, sleep, heart rate, and blood sugar. These apps might prompt us into certain behaviors, like losing weight or taking a sleeping pill. Without proper medical guidance, we may alter our behavior too much or too aggressively. (In most cases, the apps we use to assist us are commercial, so their health provenance is dubious, and they have their own goals: sell.)

IoT and IoB privacy & security concerns

The IoT itself isn’t inherently problematic; a lot of people like having their devices synced and get benefits and convenience from this setup. Instead, the concern is how we gather, navigate, and use the data, particularly at scale. And we’re starting to understand this problem.

The security and privacy consequences are complicated, and data security is a growing concern. More Americans admit that considering the security ramifications might slow their adoption and use of certain IoT devices.

To many experts, the IoT is problematic because of its lack of structure or legality. The IoB approach, interconnecting our data with our decision-making, demands change of our cultural and legal norms, which were established before the Internet and Big Data Ages.

The IoT does not gather data solely from your relationship with a single company. For instance, a car insurance company can look at a summary of your driving history. As a society, we’ve decided this is fair. But the insurers might also scour your social media profiles and interactions to “predict” whether you’re a safe driver—a questionable and extralegal move.

Importantly, it’s not just the devices themselves. Behind the scenes, many companies share (sell) data across company lines or with other subsidiaries. Google, Facebook, and Amazon continue to acquire software that potentially brings a user of a single app into their entire online ecosystem—frequently without our permission. This presents significant security and legal risks, and there is little legal protection in place for these concerns.

Benefits & pitfalls of the IoB

The bottom line is this: you don’t have to be concerned about your data. Many people accept that data is a wild west frontier, but what they get out of this is valuable. Others, however, are certainly concerned that neither companies nor government care about individual privacy.

As in our pyramid, the IoT surely converts data to information. But it’s too early to know whether the IoB can translate knowledge of us into real wisdom.