The companies succeeding in the digital age are often ones that have improved their data integration – going beyond simply collecting and mining data. These enterprises are integrating data from various, isolated silos to harness the data into business intelligence that can drive vital decision making and improves internal processes.

Data integration isn’t easy though, especially the larger your enterprise and the more software systems on which you rely. Then you consider the reality of most enterprise architecture: it is less often an intentional architecture and much more often a patchwork of various apps and ecosystems, from legacy systems to brand new tools. Some are built and owned in-house, while others rely on third-party vendors.

More and more, companies need to share data across all these systems. The problem is how difficult sharing data is when each system has different languages, requirements and protocols – and you consider the many iterations of one system talking to another.

One solution could be the canonical data model (CDM), which we are exploring in this article.

Defining CDM

Canonical data models are a type of data model that aims to present data entities and relationships in the simplest possible form in order to integrate processes across various systems and databases. More often than not, the data exchanged across various systems rely on different languages, syntax, and protocols. A CDM is also known as a common data model.

The purpose of a CDM is to enable an enterprise to create and distribute a common definition of its entire data unit. This allows for smoother integration between systems, which can improve processes, and also makes data mining easier.

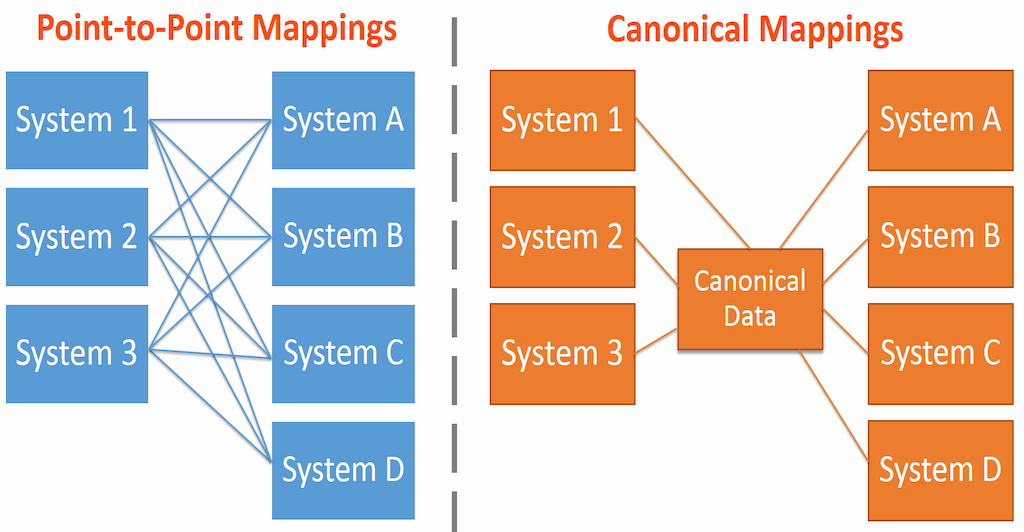

Importantly, a canonical data model is not a merge of all data models. Instead, it is a new way to model data that is different from the connected systems. This model must be able to contain and translate the other types of data. For instance, when one system needs to send data to another system, it first translates its data into the standard syntax (a canonical format or a common format) that are not the same syntax or protocol of the other system. When the second system receives data from the first system, it translates that canonical format into its own data format.

A CDM approach can and should include any technology the enterprise uses, including ESB (enterprise service bus) and BPM (business performance/process management) platforms, other SOAs (service-oriented architecture), and any range of more specific tools and applications. In its most extreme form, a canon approach would mean having one person, customer, order, product, etc., with a set of IDs, attributes, and associations that the entire enterprise can agree upon.

By employing a CDM, you are taking a canonical approach in which every application translates its data into a single, common model that all other applications also understand. This standardization is good – everyone in the company, including non-technical staff, can see that the time it takes to translate data between systems in time better spent on other projects.

Visualization of a Canonical Data Model vs Point-to-Point mappings.

Building a canonical data model

You may be tempted to use an existing data model from a connecting system as the basis of your CDM. For instance, a single, central system such as your ERP may house all sorts of data – perhaps all of your data – so it could be a decent starting point for your model.

Experts caution against this seeming short cut. If the system that is the basis of your model ever changes – even to a newer version – you may be stuck using old data models and an outdated system, which negates the benefit of the flexibility that CDMs are designed for. You may also have problems with licenses. Developers who try to handle various similar data models may also spend more time trying to decipher the differences, which can lead to more user errors.

If you’re opting for a canonical data model, it is probably your best bet to create your model from scratch. Focus on flexibility so that you reap the purpose of the CDM: easy changes as your enterprise architecture necessarily changes.

Benefits of employing a CDM

Enterprises that are able to successfully employ a CDM benefit from the following situations:

- Perform fewer translations. Without a CDM, the more systems you have, the more data translations you must do – manually. With a CDM in place, you cut down on the manual work that data integration requires and you limit the chances of user error.

- Improve translation maintenance. On an enterprise level, systems will inevitability be replaced by other systems, whether new versions or vendor SOAs that replace legacy systems. When just a single system changes, you only need to verify the translations to and from the CDM. If you’re not employing a CDM, you may spend significantly more time verifying translations to every other system.

- Improve logic maintenance. In a CDM, the logic is written within the canonical model, so there is no dependence on any other systems. Like translation maintenance, when you change out one system, you need only to verify the new system’s logic within the logic of the CDM – not with every other system that your new system may need to communicate with.

CDMs in reality

Getting a company to buy into the idea of a CDM can be difficult. Building a single data model that can accommodate multiple data protocols and languages requires an enterprise-wide approach that can take a lot of time and resources. From an executive perspective, the time and money investment may be too significant to take on unless there is a real tangible change for the end user – which may not be the case when building a CDM.

Other critics of employing CDM argue that it’s a theoretical approach that doesn’t work when applied practically. A project as large as this is often so time- and resource-consuming precisely because it is unwieldy. The inflexibility of making every service fit within a specific data model means you may lose the best case uses for some systems. These systems, in fact, may benefit from less strict specifications, not the one-size-fits-all goal of a canonical approach.

These experts recommend that an enterprise architect should instead approach the idea of a CDM differently: if you like the goal of data consistency, consider standardizing on formats and fragments of these data models – such as small XML or JSON pieces that help standardize small groupings of attributes. Less centralization will allow for independent parts to determine what’s best: teams should decide to opt into a CDM approach, instead of a top-down decision where everyone is forced to create a canon data model.

CDMs may benefit your company depending on the size and needs of your data. If you are able to spend the time on such a project, the more systems and applications that need to share data, the more elusive a one-size canonical model can be.

Original Reference Image: